Arti Patel Varanasi PhD, MPH1 | Linda Burhansstipanov DrPH, MSPH2 | Carrie Dorn MPA, LMSW3 | Sharon Gentry MSN, RN4 | Michele A. Capossela BA5 | Kyandra Fox MHA6 | Donna Wilson MSN, RN, CBCN7 | Sora Tanjasiri DrPH, MPH8 | Olayinka Odumosu BSc, MPSW, MSW, MBA9 | Elba L. Saavedra Ferrer PhD, MS10

1Advancing Synergy, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

2Native American Cancer Initiatives, Inc. (NACI), Pine, Colorado, USA

3National Association of Social Workers, Washington, DC, USA

4Academy of Oncology Nurse and Patient Navigators (AONNþ), Lewisville, North Carolina, USA

5American Cancer Society, Framingham, Massachusetts, USA

6Patient Navigation, Education and Training, Susan G. Komen Foundation, Allen, Texas, USA

7HCA Henrico Doctors' Hospital/Virginia Cancer Patient Navigator Network (VaCPNN), Midlothian, Virginia, USA

8Department of Health, Society and Behavior, University of Irvine, Irvine, California, USA

9Amorvard Services, Lagos, Nigeria

10College of Education and Human Sciences, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA

The first two authors contributed equally to this article.

Correspondence

Arti Patel Varanasi and Linda Burhansstipanov.

Email:

Varanasi AP, Burhansstipanov L, Dorn C, et al. Patient navigation job roles by levels of experience: workforce Development Task Group, National Navigation Roundtable. Cancer. 2023;1‐19. doi:10.1002/cncr.35147

Background

Oncology patient navigators (PNs) work in diverse settings from community‐based programs to comprehensive cancer centers to improve outcomes in underserved populations through timely cancer prevention, early detection, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship in a culturally appropriate and competent manner. Patient navigators assess and eliminate barriers while helping patients understand and use the health care system more effectively and efficiently.1–3 Greater standardization of navigator roles and responsibilities will lead to enhanced integration of navigators within health care teams and optimize their impact to reduce health disparities and improve sustainability of their role.4–6 The primary purpose of this article is to clarify the roles and responsibilities of PNs from Entry to Intermediate to Advanced experience levels.

Patient navigation is an evidence‐based strategy that addresses health disparities.7–11 Research indicates that PNs who are culturally congruent to the patients they serve reduce fear and anxiety, build trust, and decrease literacy and language barriers.8,12–14 They also facilitate patient–provider communication, provide psychosocial support, and manage logistical obstacles. PNs that are embedded within and trusted by their patients and communities help to bridge the gap between patients and providers, increase adherence to care recommendations, and improve quality of life and survival.8,15–25 Navigated patients are more likely than non‐navigated patients to receive timely cancer screening, treatment initiation,26 and follow‐up with diagnostic tests.15,27–31 PNs provide cancer education,32 facilitate access to care,33 improve patient satisfaction,15,34,35 assist with financial and insurance issues,36 transportation, childcare, and community resources.37 Research has suggested that patient navigation programs decrease health care costs and resource use,38 including emergency department visits39,40 and hospitalizations.41 They also assist in increasing early detection screening services and decreasing related costs.42,43 Cost analyses performed on government‐funded navigation programs show promising results.44 Despite data and evidence supporting navigation,6,8,14,16,26,45,46 sustainability of PN has been elusive.45

The American Cancer Society (ACS) created the National Navigation Roundtable (NNRT) in 2017 to initiate work on key issues around patient navigation, disseminate best practices, and enhance the field overall. The ACS NNRT is a national coalition of 80 member organizations to advance navigation efforts that eliminate barriers to quality care, reduce disparities, and foster ongoing health equity across the cancer continuum. The ACS provides leadership and expert staff support to the Roundtable.

The Workforce Development Task Group (WFD TG) is one of three within the ACS NNRT. Members include nurses, social workers, and patient navigators, who work in community and clinical settings and/or for professional navigation organizations, and administrators, researchers, and evaluators of navigation programs. During 2017– 2018, the WFD reviewed existing competencies from navigation and other similar programs throughout the United States.2 Collectively, these were refined to create the competencies used in subsequent WFD efforts. The priority for the WFD Task Group in 2019 was to define and reach consensus on the competencies for patient navigation.2

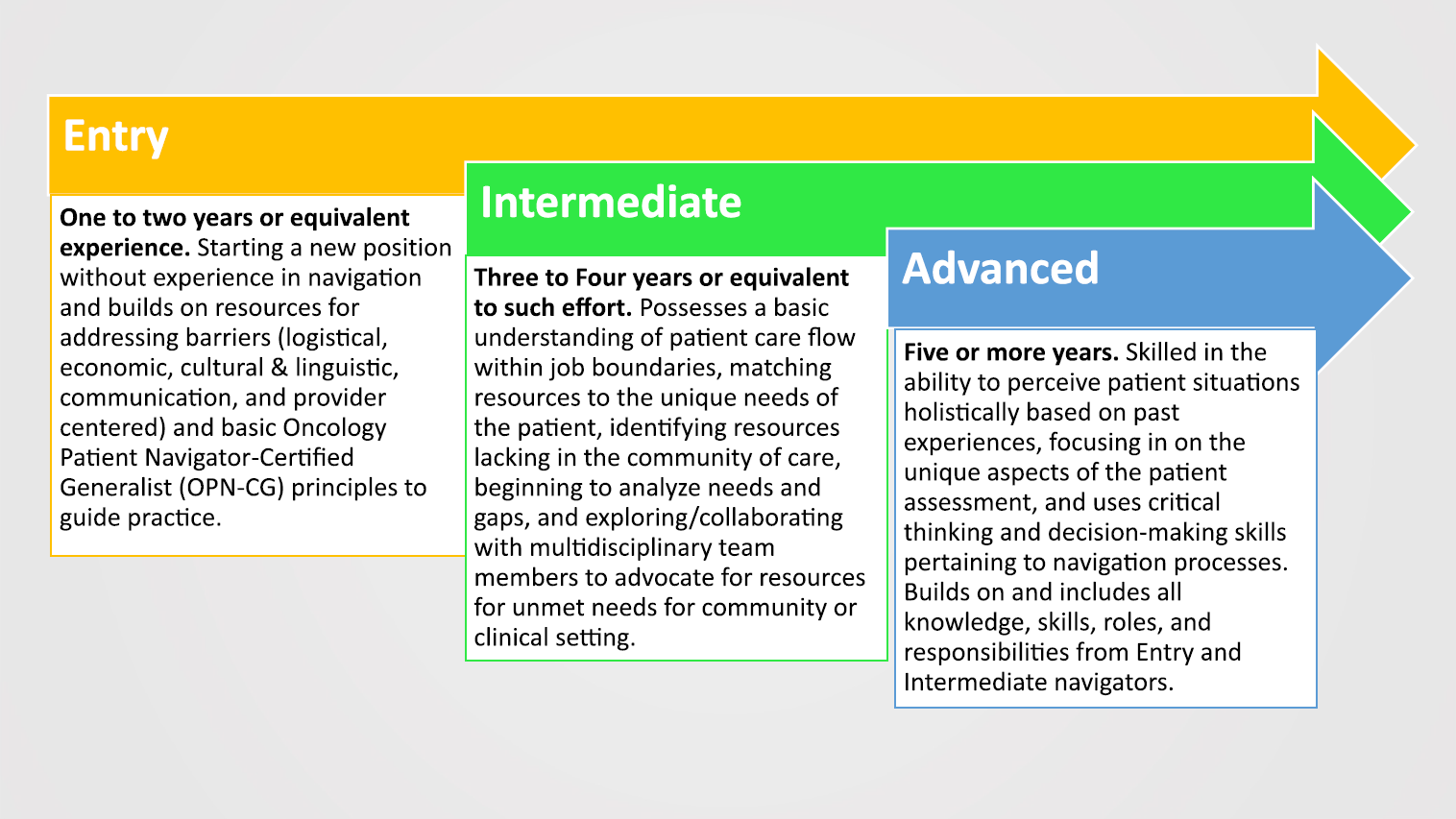

Because of the unanticipated disruptions of the COVID‐19 pandemic, ACS TGs reassessed priorities in 2020–2021. In 2022– 2023, the WFD TG decided to build on the 2019 competencies by delineating PN roles and responsibilities as a priority task. Initially, the WFD attempted to use definitions from the Oncology Nursing Society’s oncology nursing navigation website that was limited to Beginning and Advanced, but the TG felt PN required an Intermediate level. The WFD changed “Beginning” to “Entry” and defined “Entry” level as individuals with 1 to 2 years of navigation experience or equivalent and whose skills include knowledge and comprehension. For instance, the navigator may have started a new position without experience in navigation. As part of the role, the PN builds on resources for addressing logistical, economic, cultural, and linguistic, communication, patient‐, and provider‐centered barriers, and basic principles to guide practice. Entry level PNs are able to identify barriers and/or solutions but may need to obtain guidance from other members of the oncology team to whom or when to refer specific resources. In comparison, Intermediate PNs can assess barriers and identify resources independently. “Intermediate” navigators have 3 to 4 years of experience or equivalent effort, and their skills extend to application and analysis. The Intermediate PNs possess basic understanding of patient care flow within job boundaries, matching resources to the unique needs of the patient, identifying resources, analyze barriers in the community, and exploring/collaborating with multidisciplinary team members to advocate for resources for unmet needs for community or clinical setting. Entry Level PNs are learning but frequently need additional guidance from oncology nurse navigators or social workers for solutions that are more tailored to match patient needs are more efficient and effective based on their experience. “Advanced” navigators usually have 5 or more years and can evaluate patient situations holistically based on past experiences. They focus on the unique aspects of the patient assessment and use critical thinking and decision‐making skills pertaining to navigation processes. Their skills include synthesis and evaluation. Advanced navigators often contribute to program planning and communicate with internal and external stakeholders to improve organizational practices.

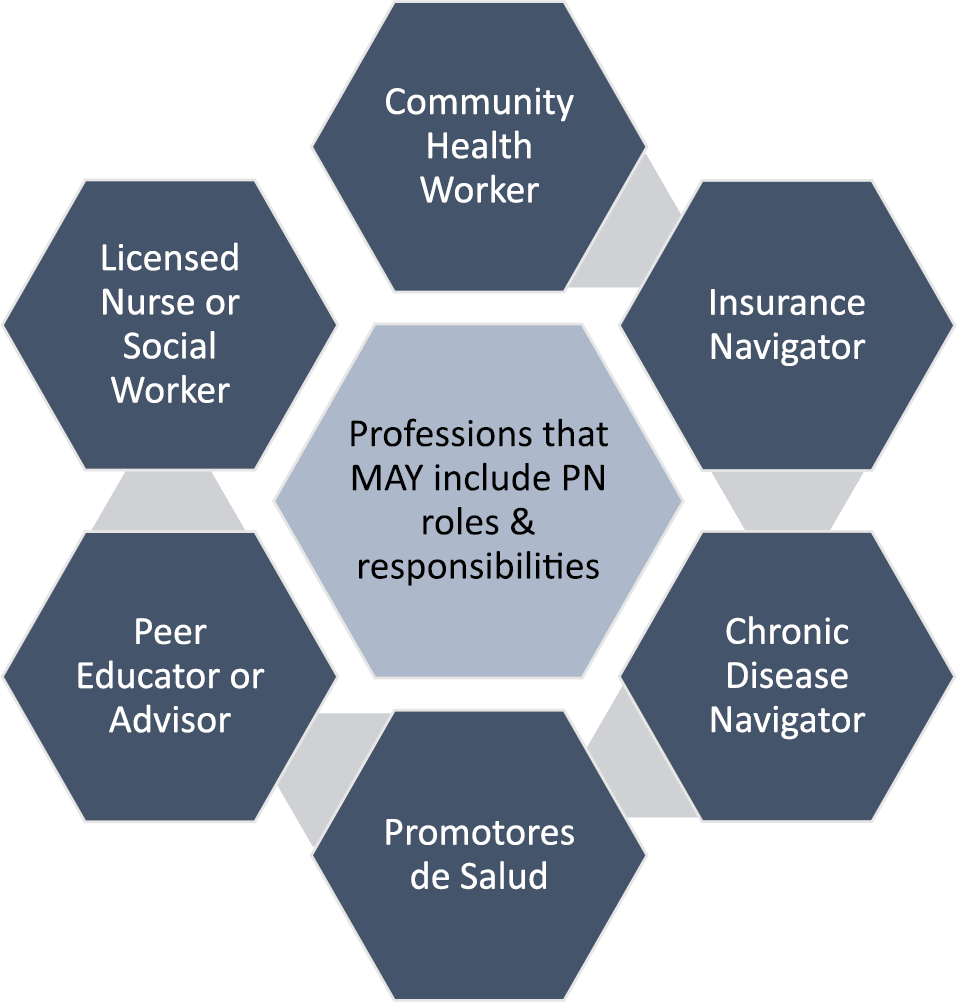

This article can be used as a resource for administrators in creating job descriptions for the navigator with specific levels of expertise. Similarly, this article can be a resource for patient navigators that are working to attain a higher level of expertise. Navigation has evolved significantly since pioneered by Harold Freeman in 1989. Through the years, various job titles were used to define this role such as cancer care liaison, care coordinator, nurse navigator, and others (Figure 1). This multitude of titles led to mixed skills and tasks in the role, limitations in comparing positions, and unclear boundaries. This ambiguity was resolved as leaders from professional oncology navigation groups created standards that included role definitions, knowledge, and skills that all professional navigators should possess to deliver high‐quality, proficient, and principled services.

In 2022, the Professional Oncology Navigation Task (PONT) group updated and obtained consensus for consistent phrasing for different types of patient navigators. According to PONT, positions that fall under the professional navigator category include oncology patient navigators and clinical navigators, defined as oncology nurse navigators and oncology social work navigators.47 Table 1 shows the PONT definitions. In contrast, this article refers to all navigator types as “patient navigators.”

Professional Navigator: A trained individual who is employed and paid by a health care, advocacy, and/or community‐based organization to fill the role of oncology navigator. Positions that fall under the professional navigator category include the following:

Oncology Patient Navigator: A professional who provides individualized assistance to patients and families affected by cancer to improve access to health care services. A patient navigator may work within the health care system at point of screening, diagnosis, treatment, or survivorship or across the cancer care spectrum or outside the health care system at a community‐based organization or as a freelance patient navigator (Academy of Oncology Nurse and Patient Navigators, 2022). A patient navigator may be employed by a clinic or a community‐based organization and work throughout the community, crossing the clinic threshold to continue to provide a consistent person of contact and support within the health care system. A patient navigator does not have or use clinical training.

Clinical Navigator (includes Oncology Nurse Navigator and Oncology Social Work Navigator):

Oncology Nurse Navigator: A professional registered nurse with oncology‐specific clinical knowledge who offers individual assistance to patients, families, and caregivers to help overcome health care system barriers. Using the nursing process, an Oncology Nurse Navigator provides education and resources to facilitate informed decision‐making and timely access to quality health and psychosocial care throughout all phases of the cancer continuum (Oncology Nursing Society, 2017).

Oncology Social Work Navigator: A professional social worker with a Masters’ degree in social work and a clinical license (or equivalent as defined by state laws) with oncology specific and clinical psychosocial knowledge who offers individual assistance to patients, families, and caregivers to help overcome health care system barriers. Using the social work process, an oncology social work navigator provides education and resources to facilitate informed decision‐making and timely access to quality health and psychosocial care throughout all phases of the cancer continuum.

Oncology Navigation: Individualized assistance offered to patients, families, and caregivers to help overcome health care system barriers and facilitate timely access to quality health and psychosocial care from pre‐diagnosis through all phases of the cancer experience (Oncology Nursing Society, Association of Oncology Social Work, and National Association of Social Workers, 2010).

Patient: (In this document) patient is used to refer to an individual screened for or diagnosed with cancer as well as their family and support systems. When working with children with cancer, both the child and the parent/legal guardian are incorporated into all aspects of care, including decision‐making.

Despite the evolution of navigation and new definitions by PONT, confusion remains about the scope of practice of PNs.47 In some settings, community‐based PNs have been requested to clean patient’s homes and run errands. Similarly, clinical navigators have been assigned administrative duties that could have been completed by administrative staff. These activities not only distract PNs from direct patient interaction, but also are examples of inappropriate job roles. There are resources available within the community that the navigator can identify and facilitate to ensure the needed services are provided. Neither licensed nor nonlicensed PNs should be doing clerical duties; their duties focus on patients.

Multiple issues and events have impacted navigation programs in the United States. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) recognized the role of patient navigation in reducing health disparities in cancer care.48 However, the ACA also used the term “patient navigators” to refer to assisters that help enroll individuals in health insurance plans. This is not the focus of oncology patient navigation with the exception that financial navigators may help patients find appropriate health insurance and other resources.4 There has been confusion between these two distinct positions.

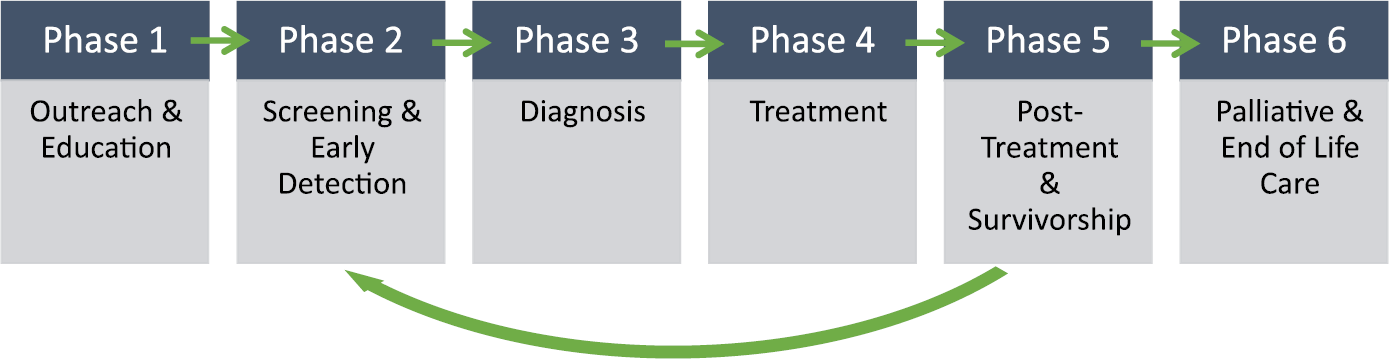

Currently, there is no Department of Labor code for patient navigation. Such a code would help differentiate between community outreach workers, Promotores/Promotoras de Salud or Community Health Workers (CHW), peer educators, patient coordinators, and other similar job positions who work with chronic conditions in addition to cancer. Among these roles, there are responsibilities that overlap, such as working with minority, underserved, and unserved individuals and cancer patients in culturally appropriate ways. Differences in navigator roles versus other similar positions include the initiation of an interaction in the community that typically continues as patients begin to engage in services within the cancer care facility. As Figure 2 shows, multiple roles may share some duties, but historically roles such as community health workers and Promotores de Salud focus on friendly, culturally respectful outreach to un‐ or underserved community members, helping them access appropriate services and care. PNs also may conduct such outreach, but they are trained to remain with the patient when they cross the clinic threshold and continue providing support throughout the full cancer continuum. The PN frequently is the most recognized face as the patient encounters 5–20 different members of the oncology health care team. Thus, the relationship with the navigator then continues throughout the cancer experience and beyond. Some patient navigators focus on a specific phase within the cancer continuum (such as screening, survivorship, or prevention) and others work with patients throughout the full continuum (prevention through end‐of‐life) (Figure 3). Few of the other roles support patients through the full continuum of care.

The COVID‐19 pandemic greatly affected the evolution of patient navigation. PNs, as well as all health care providers, were required to adjust their roles and responsibilities to address the excessive increase of COVID infections, care, recovery, and deaths. These changes in roles are described in 2022 publications.49,50

This article identifies appropriate roles and responsibilities for PNs and sets expectations for Entry, Intermediate, and Advanced navigators. This article is a compilation of experiences and insights from 12 professionals working within the field of patient navigation and members of the ACS NNRT WFD. These individuals have over 200 years of collective experience implementing, performing, training, and promoting PNs to perform multiple roles throughout the cancer continuum from outreach through end‐of‐life (Table 2, Authors' details). At the Entry, Intermediate, and Advanced levels, the competencies described in this article apply to patient navigators, nurse navigators, and social work navigators. In alliance with the PONT standards, this article and related resources should serve as a guide for all PN types and programs. It is anticipated that the WFD's recommendations on the PN job roles by level will help inform the hiring, training, and/or evaluation of PNs in the future.

| Name | Degree Title | Organization Location |

|---|---|---|

| Linda Burhansstipanov, DrPH, MSPH | President, Native American Cancer Initiatives, Inc (NACI) | Colorado |

| Michele Capossela, BA | Director Community Navigation, American Cancer Society | Massachusettes |

| Carrie Dorn, MPH, LMSW | Senior Practice Associate, National Association of Social Workers | Washington |

| Kyandra Fox, MHA | Manager, Patient Navigation, Education and Training, Susan G. Komen Foundation | Texas |

| Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN | Program Director, Academy of Oncology Nurse and Patient Navigators (AONN+) | North Carolina |

| Olayinka Odumosu, BSc, MPSW, MSW, MBA | Director, Amorvard Services | Nigeria |

| Elba L. Saavedra Ferrer, PhD, MS | Research Assistant Professor, College of Education and Human Sciences, University of New Mexico | New Mexico |

| Sora Tanjasiri, DrPH, MPH | Professor, UCI Department of Health, Society and Behavior, University of Irvine | California |

| Arti Patel Varanasi, PhD, MPH | President/CEO, Advancing Synergy | Maryland |

| Donna Richmond Wilson, RN, MSN, CBCN | Co‐Founder and Chair, HCA Henrico Doctors' Hospital, Virginia Cancer Patient Navigator Network (VaCPNN) | Virginia |

Methods

The ACS NNRT WFD convened from January 2021 through December 2022 to advance progress on the pressing PN workforce need to identify job roles specific to each PN competency,2 and clarify the topics of PN functions ranked into three experience categories: Entry, Intermediate, and Advanced. As described above, the definitions refer to number of years or “equivalent.” Equivalent refers to how many hours of experience the navigator has performed PN duties. For example, the navigator may have worked for a community or clinical‐based setting for 2 years but only provided navigation services for 100 hours. This individual would be regarded as “Entry” level. These domains and roles are guidelines. Programs can add or remove language to make the job descriptions relevant and appropriate for their local navigation program.

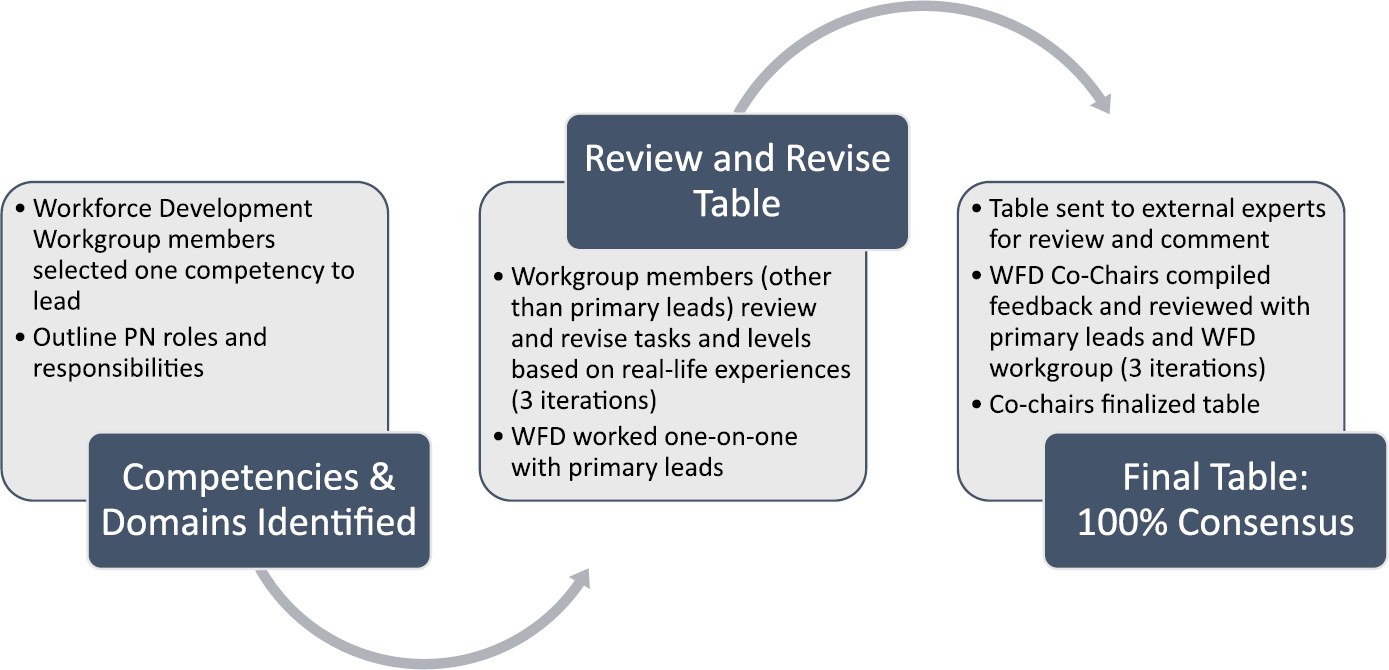

Each contributor identified a specific competency and delimited roles based on levels of expertise of the PN. The active members of WFD reviewed, critiqued, came to a consensus, and finalized the table through an iterative process (Figure 4) that involved monthly meetings, small group work sessions, and individual meetings with the WFD co‐chairs. Members talked with PNs in their respective organizations and reviewed what they could do when they entered their position as PN and what they can do now as Intermediate or Advanced PNs. These discussions helped to identify the feasibility of activities at each level. An example of a WFD discussion included one member talking about PNs picking up cleaning, doing grocery shopping and other daily activities. The WFD agreed that such activities were inappropriate for PNs at any level. A second example highlighted PN roles for administering and interpreting patient surveys and tools. The group agreed that Entry level PNs can conduct “stress distress scales” that include easy‐to‐understand interpretation scales. However, other types of tools, such as survivorship or treatment care plans, usually require more experience and assistance from other members of the health care team, such as the oncology nurse, and are grouped as Intermediate level.

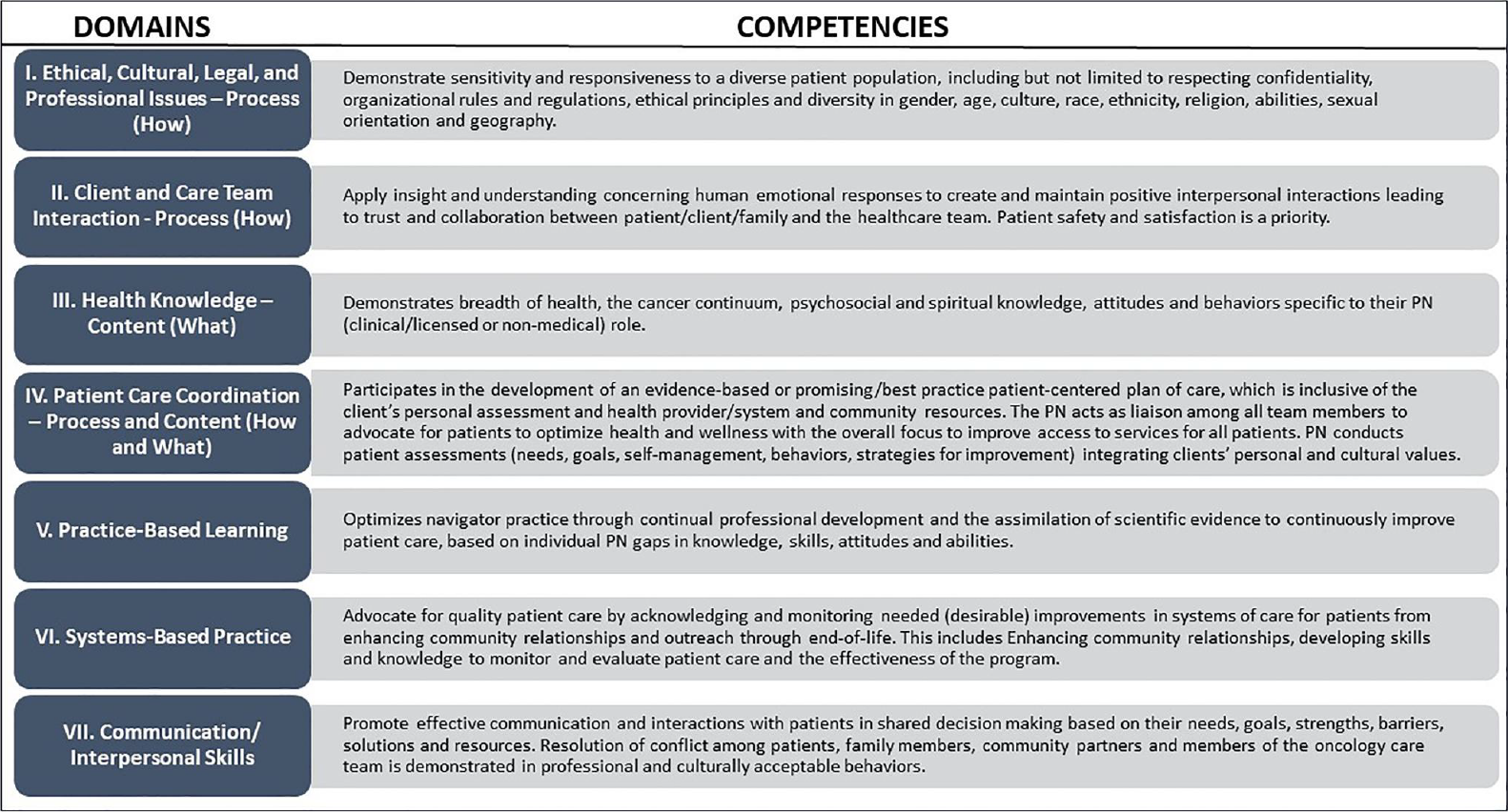

Topics were added to each row such as confidentiality, cultural knowledge, advocacy, social justice, etc. The roles specified in the “Entry” column reflected knowledge and comprehension for someone with 1 to 2 years of experience or equivalent. The skills, knowledge, and roles increased or improved to allow for application and analysis for PNs in the “Intermediate” column. Advanced PNs demonstrate significant growth in skills and roles to allow for synthesis and evaluation of information. For example, Competency I as defined in the 2019 WFD publication2 is: Demonstrate sensitivity and responsiveness to a diverse patient population, including but not limited to respecting confidentiality, organizational rules and regulations, ethical principles and diversity in gender, age, culture, race, ethnicity, religion, abilities, sexual orientation, and geography. Figure 5 shows the 2019 competencies and domains.

There are eight topics associated with this competency. As an example, the row I.2 topic is “Assessment and record keeping” and the skills required at each level are listed below.

- The Entry level job behavior is “Be cognizant of all assessments and record information that contributes to a patient’s needs, priorities, and preferences.”

- The Intermediate level job behavior is “Use assessment information to follow plans to address health and related patient needs in cooperation with the patient and based on patient priorities.”

- The Advanced level job behavior is “Develop, maintain, and utilize an organizational system to record and update health care, cultural‐relevance, health‐literacy, and linguistically appropriate resources for patients and their communities.”

Thus, for each row, there is a topic and the PN’s skill advances from Entry, to Intermediate, and then to Advanced roles. The tables reflect the professional growth of a PN through several years of experience.

Findings

The WFD resource posits a total of seven domains of competencies for PNs: I. Ethical, Cultural, Legal and Professional; II. Client and Care Team Interaction; III. Health Knowledge; IV. Patient Care Coordination; V. Practice‐Based Learning; VI. Systems‐Based Practice; and VII. Communication/Interpersonal Skills. Table 3 provides the WFD’s recommended Intermediate PN competencies, broken down by competency domain (e.g., ethical and cultural) and topics within domains (e.g., confidentiality).

ENTRY Level

I. Domain: ethical, cultural, legal, and professional issues—process (how)

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| I.1 | Confidentiality | Maintain patient confidentiality and privacy when working with clinical and professional staff both within and outside of systems of care and community‐based programs. |

| I.2 | Assessment and record keeping | Be cognizant of all assessments and record information that contributes to a patient’s needs, priorities and preferences. |

| I.3 | Help and referral | Recognize when to help, refer, and navigate the patient to appropriate health care. |

| I.4 | Cultural knowledge and behaviors | Develop, maintain, and use an organizational system to record and update health care, cultural relevance, health literacy, and linguistically appropriate resources for patients and their communities. Collect data and share with the organization leadership. |

| I.5 | Privacy laws and policies (HIPAA) | Ensure documentation complies with applicable privacy laws and policies (e.g., HIPAA). |

| I.6 | Behavior change | Understand reasons for health behavior change and patient options. |

| I.7 | Respectful behavior | Respect patients’ privacy and modesty (e.g., during a pap smear, some patients may prefer to maintain wearing a blouse or shirt). |

| I.8 | Health equity | Understand and identify ways that PN roles can increase health equity practices throughout the cancer continuum. |

II. Domain: client and care team interaction—process (how)

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| II.1 | PN role and function | Understand PN role within team and explain role and function to clinical/research staff, patients, families, and partners (e.g., community based, clinic, research, academia, and other audiences). |

| II.2 | Traditional cultural care | Learn about and respond to specific traditional/cultural care patients may use or prefer. |

| II.3 | Patient barriers and solutions | Participate in health care team discussions about ways to address patient barriers and improve overall patient care. |

| II.4 | Identifying barriers | Assist patients in identifying and documenting patients' barriers and services needed. |

| II.5 | Forms and documentation | Collaboratively and accurately complete required forms with patients, attaching required documentation, and submit to appropriate programs, staff, or organizations (e.g., needs assessment, stress‐distress surveys). |

| II.6 | Resource access |

|

| II.7 | Emotional support |

|

| II.8 | SDOH | Demonstrate an awareness of the social determinants of health and knowledge of referrals for resources to address social needs. |

| II.9 | Cultural assets | Learn and identify the cultural assets of patients and community members using a strengths‐based perspective. |

| II.10 | Social justice | Identify racism and privilege that influence health disparities. |

III. Domain: health knowledge—content (what)

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| III.1 | Use of knowledge |

|

| III.2 | Patient/caregiver education |

|

| III.3 | Health care system basics |

|

| III.4 | Prevention |

|

| III.5 | Empathy |

|

IV. Domain: patient care coordination—process and content (how and what)

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| IV.1 | Patient needs (general) | Assess clinical, emotional, spiritual, psychosocial, financial, and other patient needs. |

| IV.2 | Patient needs (insurance) | Obtain and share up‐to‐date information about health insurance programs and eligibility, public health and social service programs, and additional resources to protect and promote health. |

| IV.3 | Patient advocacy (general) | Advocate on behalf of patients and communities, as appropriate, to assist them and relevant others to attain needed care or resources in a reasonable and timely fashion.

Develop a network to support the navigator and patient. Identify barriers to care and support to eliminate barriers. |

| IV.4 | Patient advocacy (self‐determination) | Provide support for patients to follow professional caregiver instructions or advice.

Provide support, information, and referrals to caregivers. |

| IV.5 | Medical appointments and follow‐up | Schedule medical appointments on behalf of patients when appropriate.

Accompany patient to appointments when appropriate. Guide patients in getting prescriptions filled and accessing their medications. |

| IV.6 | Follow‐up care | Monitor, follow-up, and respond to change of care plan(s). |

| IV.7 | Patient documentation | Collaboratively and accurately complete required forms with patients, attaching required documentation, and submit to appropriate programs, staff, or organizations. |

| IV.8 | Care coordination (internal) | Provide information and support for people in using internal agency and/or institutional services. |

| IV.9 | Care coordination (external) | Provide information and support for patients in using external community services and resources. |

| IV.10 | Quality improvement | Provide information to agency or institution quality improvement initiatives about patients served, when appropriate. |

| IV.11 | Clinical trials | Inform patients about clinical trials and share information regarding appropriate clinical trials. |

| IV.12 | Culturally competent care coordination | Identify clinical trials resources and/or education within agency and distribute to patients. |

V. Domain: practice‐based learning

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| V.1 | Education and training |

|

| V.2 | Roles |

|

| V.3 | Privacy, respect, and legality |

|

| V.4 | Patient goals | Identify and document patient goals and communicate with the provider treatment team. |

| V.5 | Quality improvement | Identify what comprises quality improvement for the patient. |

VI. Domain: systems‐based practice

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| VI.1 | Advocacy | Advocate for care for patients. Define the role of an “advocate.” Use distress screening tool and NCCN’s Problem List. |

| VI.2 | Knowledge of resources | Knowledge of existing local, state, and national patient advocacy groups. Create and keep updated a list of key providers and contacts in the local region to which the PN can refer patients/caregivers. |

| VI.3 | Toolkits and resources | Identify appropriate toolkits and resources to assist them in their functions as PNs. Create a document with resources that can be updated. |

| VI.4 | Community Advisory Council | Become a member of the Community Advisory Council and grow membership. |

| VI.5 | Cultural competency | Identify what culturally appropriate behavior is for diverse, underserved populations. |

| VI.6 | Documentation |

|

| VI.7 | Outreach |

|

| VI.8 | Needs assessment | Assist with local and health care system community needs assessments and review previous years' assessments for content. |

VII. Domain: communication/interpersonal skills

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| VII.1 | Health equity | Demonstrate knowledge of cultural humility, implicit bias, cancer disparities among ethnic/racial and sex gender minorities and those groups that have been economically/socially marginalized. |

| VII.2 | SDOH | Demonstrate knowledge of the SDOH and their specific impact on ethnic/racial and sex gender minority populations and those groups that have been economically/socially marginalized. |

| VII.3 | Self-advocacy | Assess patient and family members/loved one’s capacity to self-advocate and communicate with their oncology team. |

| VII.4 | Community resources | Assess patient needs for community resources and services. |

| VII.5 | Interpersonal skills |

|

| VII.6 | Communication styles | Demonstrate knowledge of different communication styles, nonverbal and verbal, and culturally specific for the local patient populations. |

| VII.7 | Needs assessment | Elicit disclosure and feedback from patients so that they can communicate their needs to oncology team; conduct assessment of patient needs and goals across their cancer journey. |

| VII.8 | Outreach and engagement |

|

INTERMEDIATE

I. Domain: ethical, cultural, legal, and professional issues—process (how)

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| I.1 | Confidentiality | Demonstrate patient confidentiality and privacy when working with clinical and professional staff both within and outside of systems of care and community-based programs. |

| I.2 | Assessment and record keeping | Use assessment information to follow plans to address health and related patient needs in cooperation with the patient and based on patient priorities. Identify and collect data on key process metrics. |

| I.3 | Help and referral | Assist the patient in navigating to appropriate health care by assessing and referring patients to appropriate, culturally-relevant experts to assist with ceremonies or special services beyond one’s personal level of expertise. |

| I.4 | Cultural knowledge and behaviors | Demonstrate culturally-respectful behaviors when assisting patients with ceremonies or special services (that are pertinent to the patients’ cultural health care values, beliefs, and practices). |

| I.5 | Privacy laws and policies (HIPAA) | Develop documentation that complies with applicable privacy laws and policies (e.g., HIPAA). |

| I.6 | Behavior change | Adapt to behavior changes and patient options in a culturally-sensitive manner and be able to coach a patient through a behavior change. |

| I.7 | Respectful behavior | Demonstrate the ability to identify and suggest alternatives that respect patients’ privacy and modesty (e.g., during a pap smear, some patients may prefer to maintain wearing a blouse or shirt). |

| I.8 | Health equity | Describe ways PN roles and strategies can promote health equity throughout the cancer continuum. |

II. Domain: client and care team interaction—process (how)

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| II.2 | Traditional cultural care | Integrate specific traditional/cultural care patients may use or prefer and work with health care team to accommodate practices. |

| II.3 | Patient barriers and solutions | Participate in health care team discussions and collaborate with colleagues and partners about ways to proactively address patient barriers and improve overall patient care. |

| II.4 | Identifying barriers | Document barriers and services needed for care coordination. |

| II.5 | Forms and documentation | Collaboratively and accurately complete required forms with patients, attaching required documentation, and submit to appropriate programs, staff, or organizations. (Note: higher level, advanced forms, e.g., SCPs, efficient use of tools based within technology.) |

| II.6 | Resource Access | Assist patients with follow‐up with support programs from supporting organizations. |

| II.7 | Emotional Support | Demonstrate skill in navigating emotionally charged or high stake issues with other health care professionals, staff, patients, and families. Demonstrate skill in linking individuals and families to appropriate community and clinical resources. |

| II.8 | SDOH | Identify how the social determinants of health (poverty, transportation, safety, housing, etc.) impact a client’s ability to access health care at the individual, family, and community level. Demonstrate knowledge of referral sources to address social needs. |

| II.9 | Cultural assets | Integrate and expand understanding of cultural assets of individuals, families, and community. |

| II.10 | Social justice | Identify and combat racism and privilege that influence health disparities. Understand the relationship between public health and social justice. |

III. Domain: health knowledge—content (what)

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| III.1 | Use of knowledge |

|

| III.2 | Patient/caregiver education |

|

| III.3 | Health care system basics | Effectively use coaching techniques (e.g., teach‐back, demonstration, motivational interviewing, strength‐based statements, role playing, discussing health care language) to maximize the patient's learning and skill transfer. |

| III.4 | Prevention | Ability to facilitate educational discussion the navigator must be able to integrate and apply knowledge of cancer pathophysiology, disease process, and treatments. |

| III.5 | Empathy | Facilitate support groups for patients and/or caregivers. Provide direction of support services to patients and caregivers. |

IV. Domain: patient care coordination—process and content (how and what)

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| IV.1 | Patient needs (general) | Implement strategies that assist patients in identifying and prioritizing their personal, family, and community needs for new resources. |

| IV.2 | Patient needs (insurance) | Gather and integrate information from different sources better to understand patients, their families, and their communities. Sources may include—but are not limited to—performing interviews and researching community resources and conditions and participating in peer‐reviewed publications describing the specific population. |

| IV.3 | Patient advocacy (general) | Provide information and support for patients to advocate for themselves over time and to participate in the provision of improved services. |

| IV.4 | Patient advocacy (self‐determination) | Advocate for patients’ self‐determination, personal motivations, and dignity. |

| IV.5 | Medical appointments and follow‐up | Screen patients for issues associated with their emotional well‐being, distress, stress level, and anxiety, and provide resources as needed to reduce these stressors. |

| IV.6 | Follow‐up care | Employ a formal tool to assess risk/acuity. Re‐evaluate and update assessment regularly. |

| IV.7 | Patient documentation | Conduct education to ensure patient understands consent or other forms needed to provide quality care. |

| IV.8 | Care coordination (internal) | Apply information from patient and community assessments to develop and/or better use existing health education resources and/or strategies. |

| IV.9 | Care coordination (external) | Coordinate one’s roles with other local programs to prevent duplication of services. |

| IV.10 | Quality improvement | Engage in quality improvement initiatives. |

| IV.11 | Clinical trials | Provide referrals for clinical trials. |

| IV.12 | Culturally competent care coordination | Regularly inform patients about culturally or linguistically appropriate services and resources in agency. |

V. Domain: practice‐based learning

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| V.1 | Education and training |

|

| V.2 | Roles | Implement and clarify appropriate PN boundaries based on patient case studies and can describe strategies to help patient and members of health care team understand what does and does not fit within PN roles, including reviewing, and editing job descriptions. |

| V.3 | Privacy, respect, and legality | Obtain training that assists with documentation and follow‐up on issues related to abuse, neglect, and criminal activity that may be reportable by law and under regulation according to agency policy and report activities when required. |

| V.4 | Patient goals | Assist the patient in developing a strategic plan for attainment of personal goals. |

| V.5 | Quality improvement | Consider system processes that require improvement to benefit patients and bring to a supervisor. |

VI. Domain: systems‐based practice

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| VI.1 | Advocacy | Provide care coordination, including basic care planning (prepare questions to ask provider, treatment options clarifications) with individuals and families based on engagement and needs assessments, and facilitate care transitions. |

| VI.2 | Knowledge of resources |

|

| VI.3 | Toolkits and resources | Use PN repository of tools that are appropriate to their populations and help augment and expand toolkits related to system‐wide care coordination. |

| VI.4 | Community Advisory Council | Assume roles in Community Advisory Council (e.g., chair of a subcommittee). |

| VI.5 | Cultural competency | Shadow and integrate cultural sensitivity in all patient and health care team interactions throughout cancer continuum (e.g., diversity and inclusion). |

| VI.6 | Documentation |

|

| VI.7 | Outreach |

|

| VI.8 | Needs assessment | Conduct baseline and on‐going needs assessments of communities and their members with clearly defined goals and objectives. |

VII. Domain: communication/interpersonal skills

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| VII.1 | Health equity | Communicate effectively with patients, families/loved ones from ethnic/racially and culturally diverse groups and those that have been economically/socially marginalized by applying cultural humility. |

| V11.2 | SDOH | Identify and resolve key SDOH relevant in the care of patients and their families/loved ones from ethnic/racially and sex gender minority and those that have been economically/socially marginalized (language access, food insecurity, financial toxicity, etc.). |

| VII.3 | Self‐advocacy | Develop self‐advocacy and communication action plan with patient and family members/loved ones to improve interactions with HC team. |

| VII.4 | Community resources | Conduct timely searches of resources, reach out to community agencies to ensure appropriate alignment of patient demographics, language, health, and technology literacy. |

| VII.5 | Interpersonal skills |

|

| VII.6 | Communication styles | Assesses patient communication styles and identify sources that can assist in effective communication with the patient, family, and loved ones. |

| VII.7 | Needs assessment | Generate potential interventions based on needs assessment findings. |

| VII.8 | Outreach and engagement |

|

ADVANCED

I. Domain: ethical, cultural, legal, and professional issues—process (how)

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| I.1 | Confidentiality | Enhance processes to ensure patient confidentiality and privacy when working with clinical and professional staff both within and outside of systems of care and community‐based programs. |

| I.2 | Assessment and record keeping | Develop, maintain, and use an organizational system to record and update health care, cultural relevance, health literacy, and linguistically appropriate resources for patients and their communities. |

| I.3 | Help and referral | While (and after) the patient is receiving appropriate health care, collect interview or survey data in a culturally competent manner that complies with the given methodological design of the protocol. |

| I.4 | Cultural knowledge and behaviors | Implement cultural knowledge and sensitivity in all aspects of work, including:

|

| I.5 | Privacy laws and policies (HIPAA) | Implement policies that ensure documentation complies with applicable privacy laws and policies (e.g., HIPAA). |

| I.6 | Behavior change | Use motivational interviewing skills to effectively navigate behavior changes from patients in a culturally sensitive manner. |

| I.7 | Respectful behavior | Proactively advocate for varying ways to respect patients’ privacy and modesty (e.g., during a pap smear, some patients may prefer to maintain wearing a blouse or shirt). |

| I.8 | Health equity | Demonstrate and implement behaviors that enhance health equity behaviors while interacting with patients throughout the cancer continuum. |

II. Domain: client and care team interaction—process (how)

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| II.1 | PN role and function | Advocate for PN role sustainability among providers, administrators, stakeholders, and funders. |

| II.2 | Traditional cultural care | Advocate and be proactive in preparing health care team to accommodate traditional/cultural care patients may use or prefer to improve the effectiveness of services provided. |

| II.3 | Patient barriers and solutions | Participate in health care team discussions and program planning to advocate/proactively address patient barriers and improve overall patient care at the community/system level. |

| II.4 | Identifying barriers | Follow‐up with oncology team for resolution of barriers. |

| II.5 | Forms and documentation | Collaboratively and accurately complete required forms with patients, attaching required documentation, and submit to appropriate programs, staff, or organizations. Analyze/interpret survey findings to share trends with the health care team, administrators, stakeholders, and funders. |

| II.6 | Resource access | Build relationships with supporting organizations and maintain a good relationship with all stakeholders and organizations involved in supporting the patient treatment as they walk through survivorship. |

| II.7 | Emotional support | Model competence in navigating emotionally charged or high stake issues. Advocate for patients’ health care needs and decisions when interacting with health care professionals and systems of care. |

| II.8 | SDOH | Recommend ways that organizational practices can address the social determinants of health (e.g., food deserts, violence, poor infrastructure) at the individual, family, and community level. |

| II.9 | Cultural assets | Understand and effectively communicate cultural assets of patients, families, and community with providers, stakeholders, and funders. |

| II.10 | Social justice | Work to combat racism and privilege that influence health disparities. Using a public health perspective, understand the role of policy change in health promotion and disease prevention. |

III. Domain: health knowledge—content (what)

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| III.1 | Use of knowledge |

|

| III.2 | Patient/caregiver education |

|

| III.3 | Health care system basics |

|

| III.4 | Prevention |

|

| III.5 | Empathy | Identify social determinants of health that may impact adherence to health care services and provide interventions proactively to support the patient and caregiver. |

IV. Domain: patient care coordination—process and content (how and what)

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| IV.1 | Patient needs (general) | Develop relationships with relevant agencies and professionals in patients’ communities to secure needed care and relevant local, state, and federal organizations/resources to address health needs and inequities. |

| IV.2 | Patient needs (insurance) | Apply financial assessment that gauges a patient’s ability to achieve the best possible outcome with the least possible financial burden is a core component of navigation services. |

| IV.3 | Patient advocacy (general) | Lead and/or undertake an active role in community and agency planning to bring needed resources into the community. |

| IV.4 | Patient advocacy (self-determination) | Lead efforts to identify gaps in community resources, collaborate with other service providers, and inform policymakers. |

| IV.5 | Medical appointments and follow-up | Employ techniques for interacting sensitively and effectively with people from cultures or communities that differ from one’s own (e.g., demonstration of cultural humility in instances when cultural competence is not possible). |

| IV.6 | Follow-up care | Tailor assessment tools to identify and address unique risks and/or opportunities that consider cultural and linguistic needs and opportunities. |

| IV.7 | Patient documentation | Inform the development of forms and other documentation that use health literacy best practices to maximize patient understanding. |

| IV.8 | Care coordination (internal) | Apply assessment information to create and implement holistic approach to support patients and their families (may include participating in peer-reviewed publications describing successful practices and outcomes). |

| IV.9 | Care coordination (external) | Participate in community coalitions and/or other opportunities to coordinate services and reduce redundancies. |

| IV.10 | Quality improvement | Take leadership in identifying quality improvement opportunities as well as designing and evaluating outcomes in patients and caregivers. |

| IV.11 | Clinical trials | Collaborate with clinical trials staff to coordinate patient education and documentation on clinical trials enrollment and retention. |

| IV.12 | Culturally competent care coordination | Advocate for and promote the use of culturally and linguistically appropriate services and resources within organizations and with diverse colleagues and community partners. |

V. Domain: practice‐based learning

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| V.1 | Education and training |

|

| V.2 | Roles |

|

| V.3 | Privacy, respect, and legality | Intervene when confronted with illegal or inappropriate (e.g., privilege, racism) situations in professional manners. |

| V.4 | Patient goals | Evaluate the process for supporting the patient in attaining personal goals and recommend improvements to the navigation processes. |

| V.5 | Quality improvement | Analyze existing quality improvement initiatives and create new initiatives. |

VI. Domain: systems‐based practice

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| VI.1 | Advocacy | Share community assessment results with colleagues and community partners to inform planning and health improvement efforts. |

| VI.2 | Knowledge of resources | Participate on internal and external system-wide cancer committees, including work groups, cancer alliance, and state cancer coalitions. |

| VI.3 | Toolkits and resources | Have a leadership role in updating and refining toolkits and resources. |

| VI.4 | Community Advisory Council | Facilitate Community Advisory Council. |

| VI.5 | Cultural competency | Demonstrate cultural knowledge and sensitivity for diverse and underserved patients through supervisor's on-site observation. |

| VI.6 | Documentation |

|

| VI.7 | Outreach |

|

| VI.8 | Needs assessment | Analyze and report community priorities (based on local needs assessment) to leadership PN documentation. |

VII. Domain: communication/interpersonal skills

| Item | Topic | Tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| VII.1 | Health equity | Evaluate the health equity communication practices with patients, the health care setting, among the oncology team, and with the community to identify gaps and make improvements. |

| V11.2 | SDOH | Evaluate outcomes of how health care setting is identifying gaps and resolving key SDOH for cancer patients. |

| VII.3 | Self‐advocacy | Evaluate the processes, self‐advocacy, and communication plan and its impact on patient satisfaction. |

| VII.4 | Community resources | Evaluate processes and outcomes with community agencies to ensure patients are properly referred. |

| VII.5 | Interpersonal skills | Advance the practice of effective interpersonal skills through the practice of evaluation of interactions with patients. |

| VII.6 | Communication styles | Evaluate the delivery of different communication styles with patients and their family/loves ones to identify gaps and improve communication. |

| VII.7 | Needs assessment |

|

| VII.8 | Outreach and engagement | Share and discuss evidence‐based outreach and engagement best practices with other professionals with the intention to solve practical problems. |

Table 3 can help generate a job announcement/position for an Entry, Intermediate, or Advanced PN. Each level can be used to help generate a position description for the desired level of navigator. To do this, the reader needs to contact either of the coauthors for a password to a Google shared feedback sheet.

Table 4 can track how PN skills increase from Entry level through Intermediate to Advanced. For example, the domain for Competency III is health knowledge and the topic for the first row is “Use of Knowledge.” The following scenario illustrates the power of these distinct levels to guide PN hiring and/or promotion. For example, a PN who works with a prostate cancer patient who is receiving Lupron (leuprolide acetate for depot suspension) injections for his treatment can provide different information based on their level. The Entry level PN has basic knowledge about prostate cancer treatment and understands that Lupron is an androgen deprivation therapy that is designed to reduce prostate‐specific antigen and testosterone that subsequently reduces or prevents cancer cells from multiplying and growing. Entry level PN also understands when, where, and how the injections are administered and would need to engage additional resources, such as a clinical trials nurse, if interacting with Lupron outside of advanced prostate cancer as it is being studied in the treatment of other types of cancer, because this knowledge is outside Entry level knowledge and expertise.

| No. | Topic | Entry | Intermediate | Advanced |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| III.1 | Use of knowledge |

|

|

|

The Intermediate PNs for Competency III would know how to collect stress distress scales, conduct National Comprehensive Cancer Network problem surveys, eliminate barriers to care screening, complete social determinants of health needs assessments, and use other tools to assess the patient’s side effects, such as severe hot flashes. Based on such assessments and knowledge of the side effects of Lupron, the Intermediate PN helps the patient learn to recognize cues that increase the likelihood of hot flashes, such as eating a heavy meal. The Intermediate PN and patient collaborate on creating a plan of action to reduce the cues that set off more frequent and intense hot flashes. The Intermediate PN would obtain supervisor’s approval of the plan for safety and effectiveness.

The Advanced PN would implement and evaluate that plan of action and document additional ideas based on the analyses of the plan. The Advanced PN also would present findings about the outcomes to the plan of action to professionals and Entry and Intermediate PNs during meetings, conferences, symposia, tumor boards, and similar venues. The Advanced PN also educates, mentors, and supervises new navigators and health care team members. Such a continuum from Entry through Advanced outlines relevant PN training opportunities designed to improve their skills.

Another example for “use of knowledge” may be the Entry level PN working with a community member recently diagnosed with breast cancer. The Entry level PN can help the patient understand that a cancer diagnosis is not a death sentence and that many types of treatments are available to manage the cancer and help the patient have both high‐quality care and quantity of life following the cancer treatment experiences. The Intermediate level PN helps the patient identify her personal goals and daily behaviors that she may be ready to change (e.g., increase daily physical activity). The Advanced level PN can help the patient address severe side effects (e.g., cardiac) from treatments.

Discussion

PNs, regardless of working directly within a clinical setting or in a community‐based organization, would benefit from standardization of their established roles and functions across settings. As the field of PN expands, it is imperative that employers and health professionals understand the specific skills, knowledge, roles, and value that PNs bring to health care systems. It is essential that PNs are assigned duties applicable to their scope of work and skillset (e.g., addressing patient barriers to care). This article was designed to clarify the types of roles an employer may be able to expect from an “Entry” level PN and how those skills differ and improve for a PN who is at the “Intermediate” or “Advanced” level. Patients, families, health care teams, and PNs benefit when navigators are assigned responsibilities that are appropriate for their role and experience level. As practices are implementing and expanding navigation programs, this article can serve as a guide to decrease overlapping or inappropriate duties assigned to the PN.

PNs should be included as members of the interdisciplinary team. The navigator provides holistic approach to care delivery and focuses on care coordination, education, and physical, social, and emotional aspects of care. This holistic approach views the entire community, health care systems, and provider organizations from the patient’s perspective. Existing team members can engage PNs in conversations and meetings that promote collaboration among oncology health care providers and improve communication with and support for patients, family, and caregivers. This involvement helps demonstrate how and why PNs are valued members of the oncology care and interdisciplinary teams. The competencies described in this article can be used to support professional growth and build career ladders that correspond to years of experience. Several of the topics identified throughout the competencies are centered around health equity (including traditional culture care, social justice, cultural competence, etc.). As health systems strive to reduce health disparities, they must be cognizant of the important role that PNs serve in advancing health equity through direct patient encounters.

In conclusion, competency‐based training is essential for efficient and effective PNs. Patient navigators, regardless of their work setting need to possess competency‐based skills. The competencies developed by the WFD in 2019, were used as a foundation for the processes the WFD used to define three levels of performance based on years of experience or comparable experience into “Entry, Intermediate, and Advanced.” PN roles were organized into a table specific to competencies and levels (Tables 3 and 4). Examples of how tasks evolve for a single competency topic from Entry to Intermediate to Advanced were provided on table rows. The columns can be used to help generate a position description for the desired level of navigator. To do this, the reader needs to contact either of the coauthors for a password to a Google shared feedback sheet. The table rows help illustrate how PNs skills increase from Entry through Advanced levels.

In recognition of the Oncology Navigation Standards of Professional Practice,47 clarification of the roles and responsibilities of navigators per experience level will lead to clearer job descriptions and training and evaluation opportunities for the navigator. Standardization of navigator roles and responsibilities will lead to better integration of navigators within health care teams and improve care coordination. Clarification of PN roles could lead to tasksharing or task‐shifting with non‐navigator team members or others providing support to overcome barriers. As an example, task‐sharing occurs when both the CHW and PN may conduct outreach in respectful manners to un‐ or underserved community members. The PN is well trained on cancer knowledge, whereas the CHW is not unless it is for a specific funded grant. An example of “task shifting” occurs when the PN who has experience working with helping patients complete early detection screening (breast, cervix, colorectal, lung, and/or prostate) and is starting to work with other types of cancer. They may begin to expand knowledge to include cancers, such as lymphomas or myelomas that differ greatly from screenable cancers (i.e., expanding their learning). The PN may work with other healthcare providers who have training and experience with those cancers. The PN may also shadow colleagues to increase their understanding and comprehension of cancer site diversity. Another example of “task shifting” may be that the nurse who has been recruiting patients to screening is able to shift some of the patient load to the trained PN. The promotion of PNs to attain a higher level of expertise will lead to better integration of navigators within health care teams and improve care coordination to further address health disparities and advance health equity.

Author Contributions

Arti Patel Varanasi: Writing–original draft, writing–review and editing, and supervision. Linda Burhansstipanov: Writing–original draft, writing–review and editing, and supervision. Carrie Dorn: Writing–original draft and writing–review and editing. Sharon Gentry: Writing–original draft and writing–review and editing. Michele A. Capossela: Writing–original draft and writing–review and editing. Kyandra Fox: Writing–original draft and writing–review and editing. Donna Wilson: Writing–original draft and writing–review and editing. Sora Tanjasiri: Writing–original draft and writing– review and editing. Olayinka Odumosu: Writing–original draft and writing–review and editing. Elba L. Saavedra Ferrer: Writing–original draft and writing–review and editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the American Cancer Society National Navigation Roundtable Workforce Development Task Group.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Michele A. Capossela is employed by the American Cancer Society, which receives grants from private and corporate foundations, including foundations associated with companies in the health sector, for research outside the submitted work. Linda Burhansstipanov reports fees for professional activities from Native American Cancer Research Corporation. Sharon Gentry reports fees for professional activities from Pfizer. Donna Wilson reports fees for professional activities from Pfizer and serving as a fiduciary officer for Cancer Action Coalition of Virginia and Virginia Cancer Patient Navigator Network. Olayinka Odumosu reports serving as a fiduciary officer Amorvard Development Foundation and Amorvard Medical Services Limited. Arti Patel Varanasi reports fees for professional activities from American Cancer Society. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article because no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

ORCID

Arti Patel Varanasi https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7594-0959

Linda Burhansstipanov https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7954-3993

Sharon Gentry https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9142-0681

Donna Wilson https://orcid.org/0009-0001-6581-7615

References

- Freeman HP. Patient navigation: a community centered approach to reducing cancer mortality. J Cancer Educ. 2006;21(1 Suppl):S11‐S14. doi:10.1207/s15430154jce2101s_4

- Valverde PA, Burhansstipanov L, Patierno S, et al. Findings from the National Navigation Roundtable: a call for competency‐based patient navigation training. Cancer. 2019;125(24):4350‐4359. doi:10. 1002/cncr.32470

- Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. Patient navigation. Accessed February 9, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/screenoutcancer/ patient‐navigation.htm

- Natale‐PereiraEnard AKR, Nevarez L, Jones LA. The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer. 2011;117(S15): 3541‐3550. doi:10.1002/cncr.26264

- Dixit N, Rugo H, Burke NJ. Navigating a path to equity in cancer care: the role of patient navigation. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2021;41:1‐8. doi:10.1200/EDBK_100026

- National Navigation Roundtable Policy Task Force. Patient navigation in cancer care: review of payment models for a sustainable future. National Navigation Roundtable; 2019. Accessed November 9, 2021. http://navigationroundtable.org/wp‐content/uploads/Patient‐Navigation‐in‐Cancer‐Care‐Review‐of‐Payment‐Models_FINAL.pdf

- Gunn C, Battaglia TA, Parker VA, et al. What makes patient navigation most effective: defining useful tasks and networks. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28(2):663‐676. PMID: 28529216. doi:10.1353/hpu.2017.0066

- Krebs LU, Burhansstipanov L, Watanabe‐Galloway S, Pingatore NL, Petereit DG, Isham D. Navigation as an intervention to eliminate disparities in American Indian communities. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2013;29(2):118‐127. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2013.02.007

- Louart S, Bonnet E, Ridde V. Is patient navigation a solution to the problem of "leaving no one behind"? A scoping review of evidence from low‐income countries. Health Pol Plann. 2021;36(1):101‐116. doi:10.1093/heapol/czaa093

- Louart S, Bonnet E, Kadio K, Ridde V. How could patient navigation help promote health equity in sub‐Saharan Africa? A qualitative study among public health experts. Glob Health Promot. 2021; 28(1_Suppl l):75‐85. doi:10.1177/1757975920980723

- Parry J, Vanstone M, Grignon M, Dunn JR. Primary care‐based interventions to address the financial needs of patients experiencing poverty: a scoping review of the literature. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):219. doi:10.1186/s12939‐021‐01546‐8

- Braun KL, Kagawa‐Singer M, Holden AE, et al. Cancer patient navigator tasks across the cancer care continuum. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(1):398‐413. doi:10.1353/hpu.2012.0029

- Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, et al. Patient navigation: state of the art or is it science? Cancer. 2008;113(8):1999‐2010. doi:10. 1002/cncr.23815

- Wilcox B, Bruce SD. Patient navigation: a "win‐win" for all involved. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(1):21‐25. doi:10.1188/10.ONF.21‐25

- Harjo LD, Burhansstipanov L, Lindstrom D. Rationale for "cultural" native patient navigators in Indian country. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29(3):414‐419. doi:10.1007/s13187‐014‐0684‐0

- Tang KL, Kelly J, Sharma N, Ghali WA. Patient navigation programs in Alberta, Canada: an environmental scan. CMAJ Open. 2021;9(3):E841‐E847. Published 2021 Sep 7. doi:10.9778/cmajo. 20210004

- Doucet S, Luke A, Splane J, Azar R. Patient navigation as an approach to improve the integration of care: the case of NaviCare/ SoinsNavi. Int J Integrated Care. 2019;19(4):7. doi:10.5334/ijic.4648

- Reid AE, Doucet S, Luke A, Azar R, Horsman AR. The impact of patient navigation: a scoping review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2019;17(6):1079‐1085. doi:10.11124/JBISRIR‐2017‐003958

- Carter N, Valaitis RK, Lam A, Feather J, Nicholl J, Cleghorn L. Navigation delivery models and roles of navigators in primary care: a scoping literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):96. doi:10.1186/s12913‐018‐2889‐0

- McBrien KA, Ivers N, Barnieh L, et al. Patient navigators for people with chronic disease: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13(2): e0191980. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191980

- Peart A, Lewis V, Brown T, Russell G. Patient navigators facilitating access to primary care: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3): e019252. doi:10.1136/bmjopen‐2017‐019252

- Matousek AC, Addington SR, Kahan J, et al. Patient navigation by community health workers increases access to surgical care in rural Haiti. World J Surg. 2017;41(12):3025‐3030. doi:10.1007/s00268‐017‐4246‐6

- Valaitis RK, Carter N, Lam A, Nicholl J, Feather J, Cleghorn L. Implementation and maintenance of patient navigation programs linking primary care with community‐based health and social services: a scoping literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):116. doi:10.1186/s12913‐017‐2046‐1

- dela Riva EE, Hajjar N, Tom LS, Phillips S, Dong X, Simon MA. Providers' views on a community‐wide patient navigation program: implications for dissemination and future implementation. Health Promot Pract. 2016;17(3):382‐390. doi:10.1177/1524839916628865

- Ko NY, Snyder FR, Raich PC, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in patient navigation: results from the Patient Navigation Research Program. Cancer. 2016;122(17):2715‐2722. doi:10.1002/cncr.30109

- Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, et al. Impact of patient navigation on timely cancer care: the Patient Navigation Research Program. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(6):dju115. doi:10.1093/jnci/dju115

- Ferrante JM, Chen PH, Kim S. The effect of patient navigation on time to diagnosis, anxiety, and satisfaction in urban minority women with abnormal mammograms: a randomized controlled trial. J Urban Health. 2008;85(1):114‐124. doi:10.1007/s11524‐007‐9228‐9

- Robinson‐White S, Conroy B, Slavish KH, Rosenzweig M. Patient navigation in breast cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33(2):127‐140. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181c40401

- Braun KL, Thomas WL Jr, Domingo JL, et al. Reducing cancer screening disparities in medicare beneficiaries through cancer patient navigation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(2):365‐370. doi:10.1111/jgs.13192

- Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A, Jandorf L, Itzkowitz SH. Cost‐effectiveness of patient navigation to increase adherence with screening colonoscopy among minority individuals. Cancer. 2015;121(7):1088‐1097. doi:10.1002/cncr.29162

- Taylor VM, Hislop TG, Jackson JC, et al. A randomized controlled trial of interventions to promote cervical cancer screening among Chinese women in North America. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(9):670‐677. doi:10.1093/jnci/94.9.670

- Wang ML, Gallivan L, Lemon SC, et al. Navigating to health: evaluation of a community health center patient navigation program. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:664‐668. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.08.002

- Roland KB, Milliken EL, Rohan EA, et al. Use of community health workers and patient navigators to improve cancer outcomes among patients served by federally qualified health centers: a systematic literature review. Health Equity. 2017;1(1):61‐76. doi:10.1089/heq.2017.0001

- Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer. 2011;117(15 suppl):3539‐3542. doi:10.1002/cncr.26262

- Jean‐Pierre P, Cheng Y, Wells KJ, et al. Satisfaction with cancer care among underserved racial‐ethnic minorities and lower‐income patients receiving patient navigation. Cancer. 2016;122(7):1060‐1067. doi:10.1002/cncr.29902

- Darnell JS. Navigators and assisters: two case management roles for social workers in the Affordable Care Act. Health Soc Work. 2013;38(2):123‐126. doi:10.1093/hsw/hlt003

- Chowdhury AM. Rethinking interventions for women's health. Lancet. 2007;370(9595):1292‐1293. doi:10.1016/S0140‐6736(07)61554‐2

- Enard KR, Ganelin DM. Reducing preventable emergency department utilization and costs by using community health workers as patient navigators. J Healthc Manag. 2013;58(6):412‐428. doi:10.1097/00115514‐201311000‐00007

- Horyna TJ, Jimenez R, McMurry L, Buscemi D, Cherry B, Seifert CF. An evaluation of interprofessional patient navigation services in high utilizers at a county tertiary teaching health system. J Healthc Manag. 2020;65(1):62‐70. doi:10.1097/JHM‐D‐19‐00123

- Thompson MP, Podila PSB, Clay C, et al. Community navigators reduce hospital utilization in super‐utilizers. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(2):70‐76.

- Seaberg D, Elseroad S, Dumas M, et al. Patient navigation for patients frequently visiting the emergency department: a randomized, controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(11):1327‐1333. doi:10.1111/acem.13280

- Li Y, Carlson E, Villarreal R, Meraz L, Pagán JA. Cost‐effectiveness of a patient navigation program to improve cervical cancer screening. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(7):429‐434.

- Shih YC, Chien CR, Moguel R, Hernandez M, Hajek RA, Jones LA. Cost‐effectiveness analysis of a capitated patient navigation program for medicare beneficiaries with lung cancer. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(2):746‐767. doi:10.1111/1475‐6773.12333

- Bensink ME, Ramsey SD, Battaglia T, et al. Costs and outcomes evaluation of patient navigation after abnormal cancer screening: evidence from the Patient Navigation Research Program. Cancer. 2014;120(4):570‐578. doi:10.1002/cncr.28438

- Dwyer AJ, Wender RC, Weltzien ES, et al. Collective pursuit for equity in cancer care: the National Navigation Roundtable. Cancer. 2022;128(Suppl 13):2561‐2567. doi:10.1002/cncr.34162

- Fleisher L, Miller SM, Crookes D, et al. Implementation of a theorybased, non‐clinical patient navigator program to address barriers in an urban cancer center setting. J Oncol Navig Surviv. 2012;3(3):14‐23.

- Professional Oncology Navigation Task Force Releases Oncology Navigation Standards of Professional Practice, Published March 2022. Accessed February 20, 2023. https://aonnonline.org/press/4463‐professional‐oncology‐navigation‐task‐force‐releases‐oncologynavigation‐standards‐of‐professional‐practice‐2022

- Moy B, Chabner BA. Patient navigator programs, cancer disparities, and the patient protection and affordable care act. Oncologist. 2011;16(7):926‐929. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2011‐0140

- Valverde PA, Kennedy Sheldon L, Gentry S, Dwyer AJ, Saavedra Ferrer EL, Wightman PD. Flexibility, adaptation, and roles of patient navigators in oncology during COVID‐19. Cancer. 2022;128(suppl 13):2610‐2622. doi:10.1002/cncr.33962

- Wells KJ, Dwyer AJ, Calhoun E, Valverde PA. Community health workers and non‐clinical patient navigators: A critical COVID‐19 pandemic workforce. Prev Med. 2021;146:106464. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106464

How to cite this article:

Varanasi AP, Burhansstipanov L,

Dorn C, et al. Patient navigation job roles by levels of

experience: workforce Development Task Group, National

Navigation Roundtable. Cancer. 2023;1‐19. doi:10.1002/cncr.35147